I never thought the practice of on-location drawing, especially as a group, could have a social purpose, but a recent experience in Caracas proved me wrong.

I had the opportunity to visit the capital of Venezuela earlier this month as a guest speaker of “Dibuja Caracas,” (“Draw Caracas,” in English) an event sponsored by Faber-Castell as part of their social responsibility programs —who knew a pen manufacturer would even have such programs? The event was organized by Euro Trading, Faber’s distributor in Venezuela, and Sinergia Global, a local marketing firm.

The idea behind Dibuja Caracas was to draw attention to Faber-Castell’s 250th anniversary and energize the community with two days of urban sketching activities.

More than 100 locals attended this “1st Urban Sketching Meet-up: Lines, Drawings and Brushstrokes of Caracas,” as the event was advertised (Primer Encuentro de Dibujo Urbano. Trazos, Dibujos y Pinceladas de Caracas).

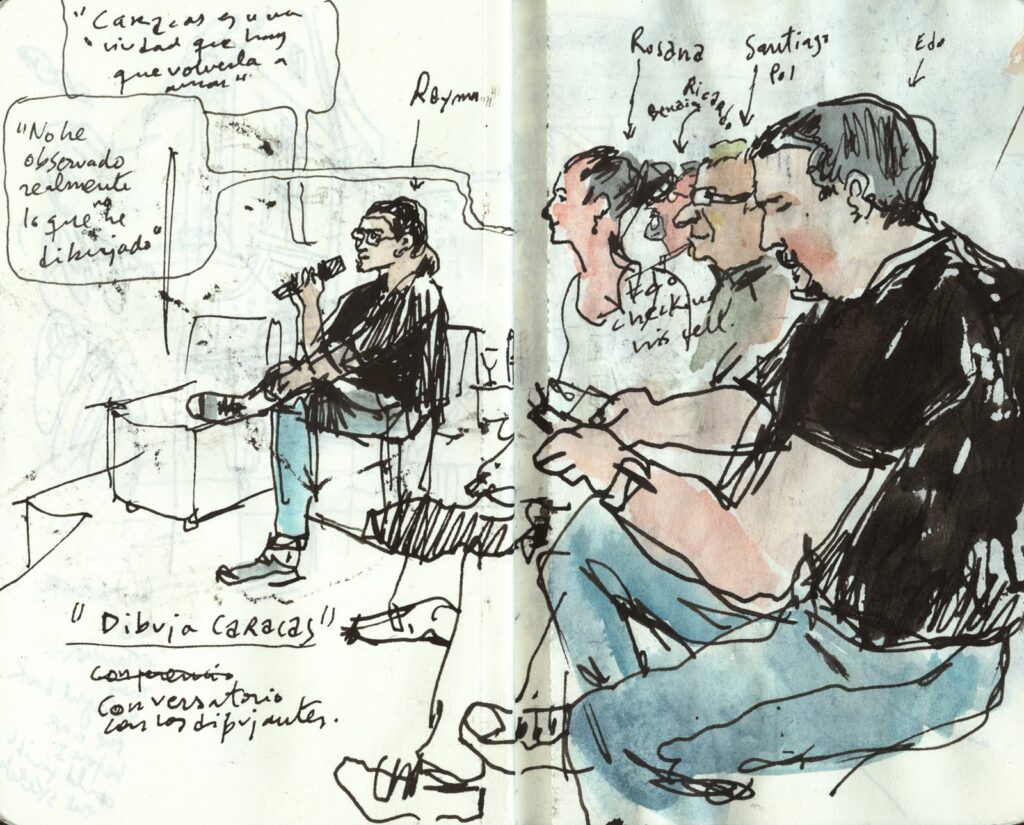

The program started with my talk about the Urban Sketchers movement on Friday, Dec. 2, followed by a panel on urban sketching with a group of well-known Venezuelan artists: Rayma, editorial cartoonist of El Universal, Edo Sanabria, caricaturist and cartoonist of newspaper El Mundo, children’s books illustrator Rosana Faría, sculptor and artist Ricardo Benaim and graphic designer Santiago Pol.

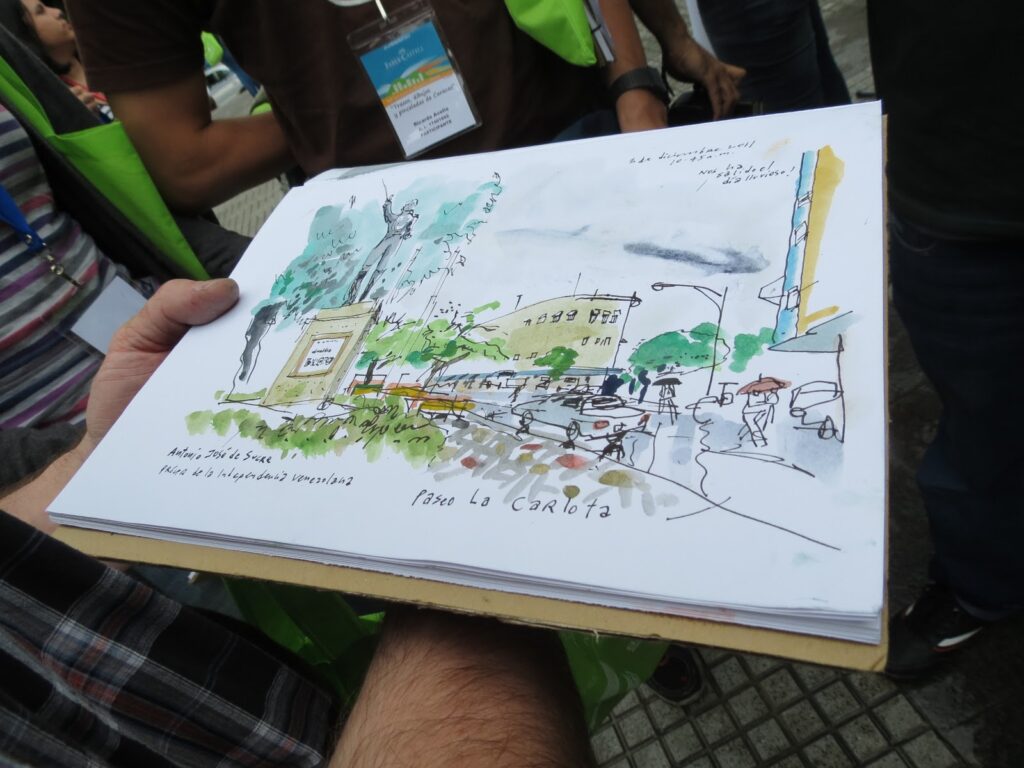

The next day, Saturday, Dec. 3, was devoted to drawing in four distinctive districts of Caracas: Libertador, Baruta, Sucre, and Chacao, where the event had its base camp at Plaza Los Palos Grandes. We were taken to the different sketching locations by bus and returned to Chacao for the closing exhibit, when all the drawings we had made were displayed from a laundry line in the middle of the square to the delight of participants and passers-by.

Judging by the smiles I saw and what some participants told me, the event exceeded their expectations. It meant much more than getting a nice goodie bag full of free pens and going out to draw. It meant claiming back the beautiful Caracas they seem to have forgotten amid the rising crime and uncontrollable growth of shanty towns surrounding this metropoli. That Caracas they can’t enjoy because it’s too risky to walk on the street by yourself — according to an article in El Universal, 472 people were killed in the streets of Caracas in November alone, 80 percent of them by gun fire. That explains why people drive with their windows up for fear of being robbed, even kidnapped. Or why it’s better to run a red light at night than to stop and face the risk of being assaulted at the intersection, as the driver who took me from the airport to the hotel did several times.

“We really needed something like this event” told me Santiago Pol. Sketching is going to help us see the beautiful side of Caracas (“lo bello de Caracas,”) he added, thanking me for being there to help them spread that message.

What Pol and other participants were telling me is something I had never thought of, that with our pens and sketchbooks we can reclaim the public space lost to crime or abandoned to anarchy. What a noble goal, right?

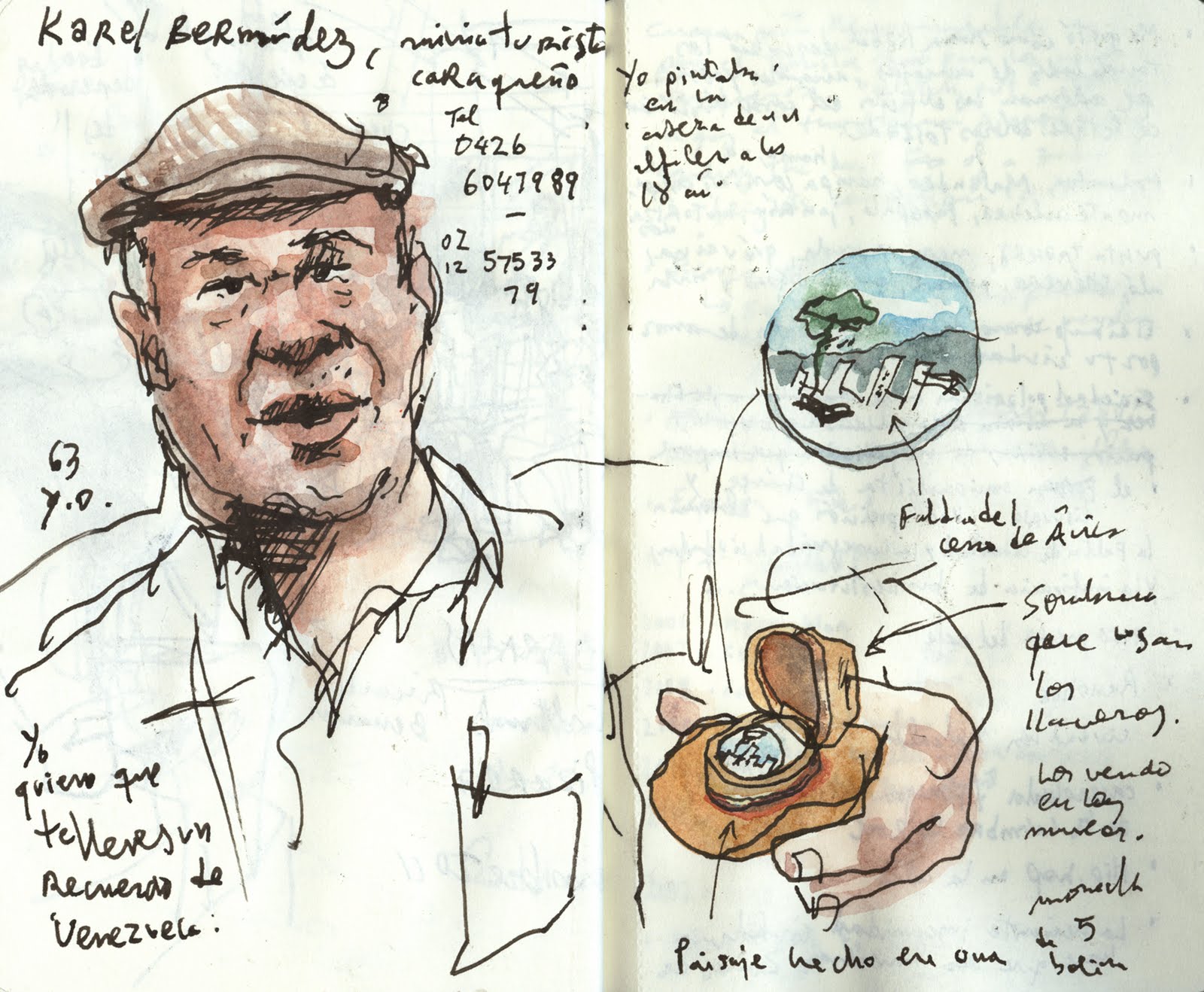

Here are some other highlights and drawings I made during my stay in Caracas, which unfolded under unusual gray skies brought in by tropical storms — “We just wanted you to feel like in Seattle,” quipped one of the organizers to justify the weather.

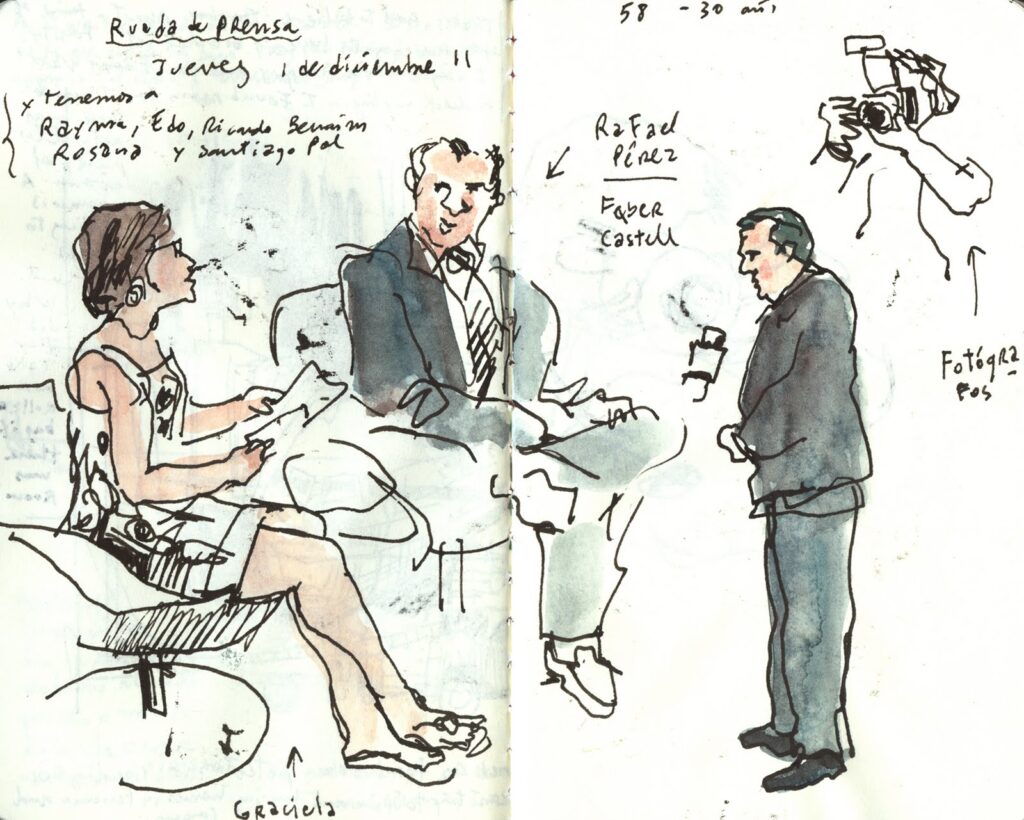

A day before the event started, local and national media were invited to a press conference on the penthouse of Hotel Pestana, the tony hotel in the district of Chacao where I stayed. The trendy atmosphere by the swimming pool on the 18th floor struck me as an oasis of luxury in the middle of the city. As for the media attention, I didn’t quite know what to make of it, but I did my best to represent the global urban sketching movement that served the inspiration to Dibuja Caracas. (The event’s lead organizer, Sinergia’s Carmen Yolanda Moreno, had come across Urban Sketchers on Facebook through her brother-in-law, an urban sketcher from Italy named Marco Pallini, when working on proposals for Faber-Castell. That’s how the idea of an urban sketching event in Caracas started.)

Helping Carmen with the promotion of the event was Graciela Beltrán Carias, a popular broadcast journalist. Graciela also interviewed me later in the day during her daily show at Onda 107.9 FM.

Stories announcing “Dibuja Caracas” appeared in the most circulated Venezuelan newspapers the next day.

José “Cheo” Carvajal, a local journalist who writes a weekly column, “Caracas on foot,” (Caracas a pie) for El Nacional newspaper, gave me a tour of several Caracas neighborhoods on Friday morning. I couldn’t have had a better guide than this pedestrian advocate who took me through parts of the city I wouldn’t have dared to visit on my own.

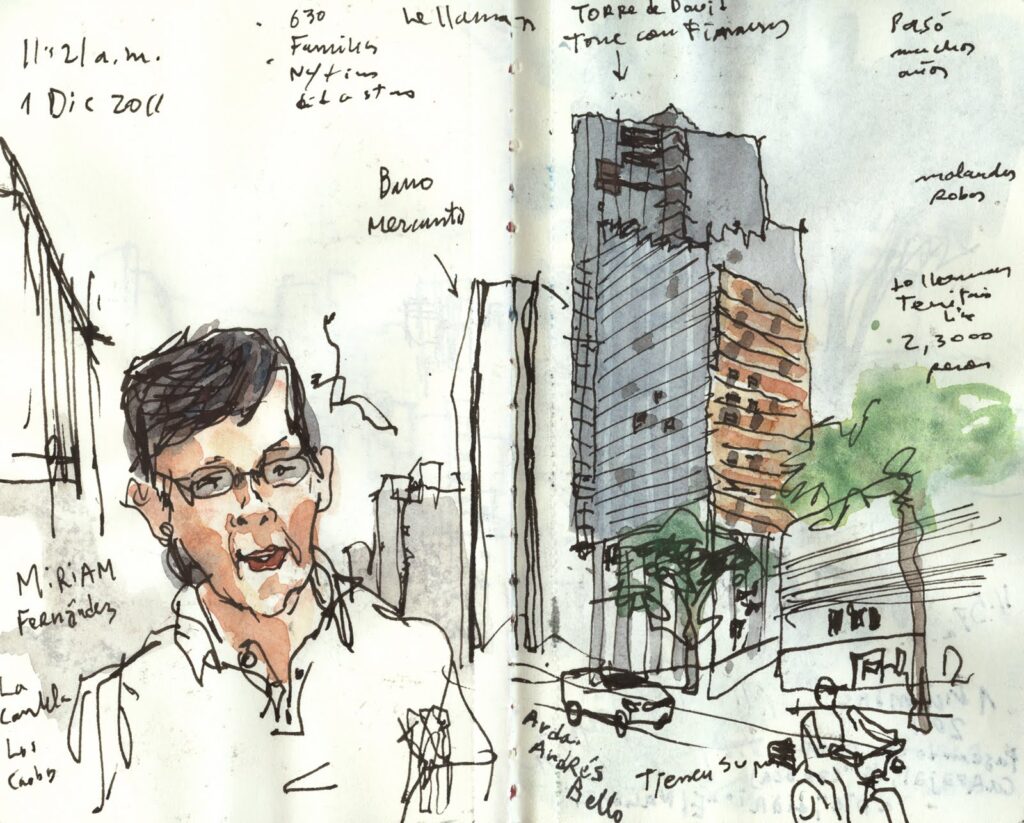

At Avenida Andrés Bello, I stopped to sketch “La Torre Confinanzas,” the third tallest skyscraper in Caracas. Cheo explained that it was a bank that never got finished and, after the government expropriated it, squatters moved in and created their own “city” inside. If you’ve ever wondered what anarchy could look like, this tower exemplifies it. Occupiers have fixed it up doing what Cheo described as “urban mining.” Street debris and other’s people junk becomes raw material for the building needs of the squatters.

As I sketched, a woman approached me to ask if I was part of “Dibuja Caracas.” Someone is reading those newspapers I thought. And that was the case. Miriam Fernández had seen one of the stories published. I took the opportunity to ask her about the building and she shared her disbelief about its fate. She said the tower is now known as a “territorio libre,” a free territory, where more than 2,000 people live. A guard we spoke to later at the entrance of the tower said 630 families live in it.